A podcast for Midwesterners

Kyle Kuphal | Staff reporter

kkuphal@pipestonestar.com

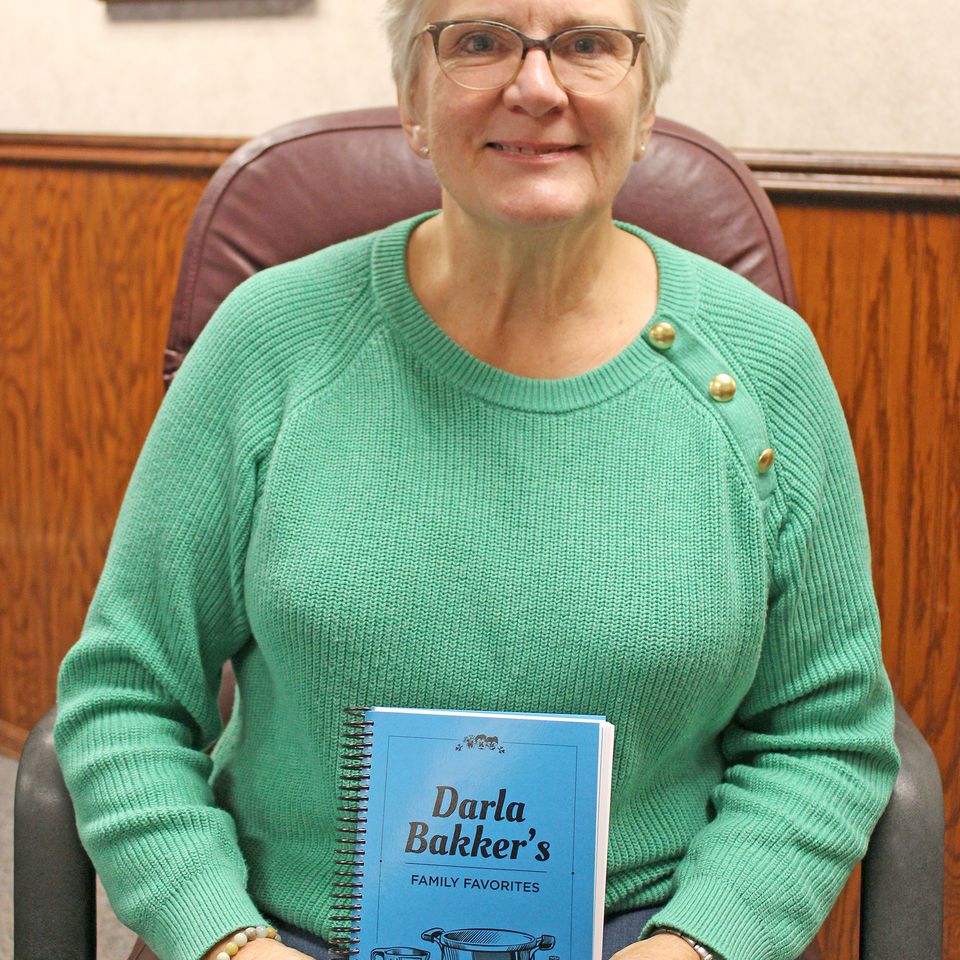

Staci Mergenthal, of Lake Benton, is the host of a podcast called “Funeral Potatoes & Wool Mittens.”

Mergenthal started the podcast in December of 2022. She said she chose the name because she wanted something different that people would remember. The funeral potatoes, or cheesy hash browns, represent a comfort and community vibe, she said, and the wool mittens represent the Midwest, cold weather and coziness. In the beginning of her podcast she describes it as “a show for people who embrace the warm and cozy spirit of everyday living in the Midwest.”

Mergenthal has a background in corporate communications and freelance writing for magazines. She’s also done some private baking for individuals, fundraisers and weddings. About 15 years ago, she started a blog as a place to share recipes. She started the podcast because she wanted to listen to one like it and couldn’t find any.

“For all my life, I’ve really just learned to cook and bake and love it from other home bakers and cooks — just everyday people, not chefs,” Mergenthal said. “I’m not big into the big fancy culinary chefs. I’m not a culinary person or trained, but have always loved to learn from grandmas and aunts. I wanted to listen to a podcast like that and all I could ever find was the famous people, the popular chefs, restaurant owners, which is great. They’re incredible and it’s wonderful, but that’s just not necessarily how I learn or what I like.”

Early on, she did some podcasts alone, then she did a few episodes with her husband, Jason, and then other family members and friends. She’s since interviewed guests from Minnesota, South Dakota, North Dakota, Iowa, Wisconsin and Michigan, often by Zoom. They’ve included greenhouse owners, an Airbnb owner, honey farmers, cattle ranchers, popcorn store owners, waffle makers, a high school student who grew and gave away garden produce, interior designers, an author, a volunteer birthday cake baker, Christmas tree farm owners, museum staff and more. No matter who the guest is, the conversation usually includes food.

“You can talk to anybody and you can be talking about anything,” Mergenthal said. “They could be a perfect stranger and you still could end up back on that topic.”

Her guests are typically people she’s heard about from others, read about or seen in the news. She also welcomes story ideas, which can be sent to her at staci@randomsweets.com.

In addition to her podcast and blog, Mergenthal can be seen on KELOLAND Living discussing recipes and food. She’s a member of the South Dakota State University Communication and Journalism Advisory Board, East Central Court Appointed Special Advocates Board in Brookings and the Lake Benton Public Library Board.

Mergenthal’s blog, podcast, recipes and more are available at randomsweets.com. The podcast is also found on other platforms where podcasts are found.

kkuphal@pipestonestar.com

Staci Mergenthal, of Lake Benton, is the host of a podcast called “Funeral Potatoes & Wool Mittens.”

Mergenthal started the podcast in December of 2022. She said she chose the name because she wanted something different that people would remember. The funeral potatoes, or cheesy hash browns, represent a comfort and community vibe, she said, and the wool mittens represent the Midwest, cold weather and coziness. In the beginning of her podcast she describes it as “a show for people who embrace the warm and cozy spirit of everyday living in the Midwest.”

Mergenthal has a background in corporate communications and freelance writing for magazines. She’s also done some private baking for individuals, fundraisers and weddings. About 15 years ago, she started a blog as a place to share recipes. She started the podcast because she wanted to listen to one like it and couldn’t find any.

“For all my life, I’ve really just learned to cook and bake and love it from other home bakers and cooks — just everyday people, not chefs,” Mergenthal said. “I’m not big into the big fancy culinary chefs. I’m not a culinary person or trained, but have always loved to learn from grandmas and aunts. I wanted to listen to a podcast like that and all I could ever find was the famous people, the popular chefs, restaurant owners, which is great. They’re incredible and it’s wonderful, but that’s just not necessarily how I learn or what I like.”

Early on, she did some podcasts alone, then she did a few episodes with her husband, Jason, and then other family members and friends. She’s since interviewed guests from Minnesota, South Dakota, North Dakota, Iowa, Wisconsin and Michigan, often by Zoom. They’ve included greenhouse owners, an Airbnb owner, honey farmers, cattle ranchers, popcorn store owners, waffle makers, a high school student who grew and gave away garden produce, interior designers, an author, a volunteer birthday cake baker, Christmas tree farm owners, museum staff and more. No matter who the guest is, the conversation usually includes food.

“You can talk to anybody and you can be talking about anything,” Mergenthal said. “They could be a perfect stranger and you still could end up back on that topic.”

Her guests are typically people she’s heard about from others, read about or seen in the news. She also welcomes story ideas, which can be sent to her at staci@randomsweets.com.

In addition to her podcast and blog, Mergenthal can be seen on KELOLAND Living discussing recipes and food. She’s a member of the South Dakota State University Communication and Journalism Advisory Board, East Central Court Appointed Special Advocates Board in Brookings and the Lake Benton Public Library Board.

Mergenthal’s blog, podcast, recipes and more are available at randomsweets.com. The podcast is also found on other platforms where podcasts are found.